- Behaviour Primary

- >

- Heart Master’s Coping Cards

SKU:

Ref:321W

Heart Master’s Coping Cards

£26.99

£26.99

Unavailable

per item

The Heart Master’s Coping Cards are designed to encourage reflection about the many ways people cope with change, and the body’s way of adapting to change.

The Heart Masters: Coping cards provide a comprehensive set of activities about: • Stress • Behaviour Change • Study Habits

Includes Many ideas about how to use the cards are included in the booklet as part of the activities.

The cards have been humorously cartooned by Adrian Osborne to capture the attention of young people.

Contains 30 A6 cards and instruction booklet

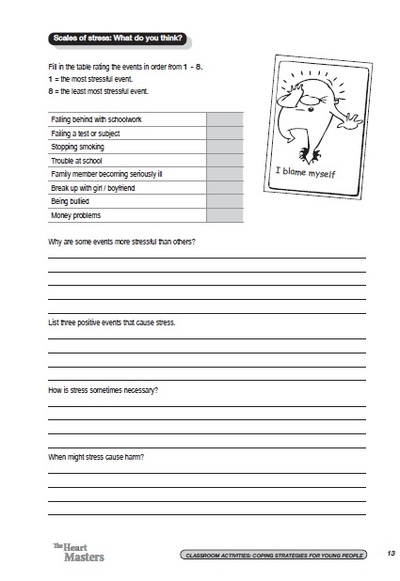

Sample of cards |

A number of years ago, the late Dr Chris Madden was working as a clinical psychologist at a psychiatric hospital with patients who had a limited repertoire when responding to stress. They had substance addictions. As they fell deeper into their addiction, the alcohol and other drugs were not only a response to stress, they were the cause of it. Patients could not imagine life without a substance, but life with the substance was also intolerable.

Chris began to think about coping styles in terms of helpful and unhelpful. Using alcohol and other drugs in harmful ways to relieve stress was clearly an unhelpful coping strategy. For many dependent users, it had dominated, and even destroyed their lives. Working with these people, made Chris wonder about the coping strategies of young people. He believed that coping styles were learned. Some people learned predominantly helpful coping styles. As they became older, they became more proficient at managing their stress and their inter-actions with the rest of the world. Unfortunately for others, like the drug dependent patients with whom Chris was working, they learned predominantly unhelpful coping strategies. Their lives became increasingly difficult.

Chris decided to do some research with young people. Unfortunately, Chris passed away before his research could be published but nevertheless his findings provide an insight into helping young people. After interviewing nearly three hundred 15 year old students, Chris concluded there were basically eight (8) styles of coping. These are listed below, with short statements that characterise those styles.

Philosophical coping

• I try to see the funny side of things.

• I try to believe positive or good things about myself.

Problem-focused coping

• I just set my mind on what I had to do next.

• I tried to change the mind of the person in control of the situation.

Self-blame / culpability

• I realise I caused the problem.

• I kept others from knowing how bad things were.

Denial

• I tried to keep my feelings to myself.

• I went on as if nothing had happened.

Orientation to others

• I talked to someone to find out more about the situation.

• I tried to help others who were in need of help.

Self-care

• I tried to get plenty of sleep.

Acting out / loss of patience

• I was angry with those who caused the situation.

• I tried to make myself feel better by eating, drinking alcohol, smoking, using drugs or medication.

Composure

• I didn’t let the situation get to me.

• I made myself not worry or be upset.

The first implication is important in terms of managing the behaviour of young people. When discussing a young person’s behaviour, adults often refer to the behaviour as good or bad. This is a moral judgement. However, rather than interpret this as a judgement about behaviour, young people tend to interpret moral judgement as about them, the person. In other words, they are either intrinsically good or bad.

Instead of passing moral judgements, parents and teachers will be more effective if they engage in a discussion about choice. They can best do this when they have helped young people to understand how they construct their behaviour. A useful starting point is to borrow an equation from the field of rational / emotive therapy. It is simply: an event + an interpretation = a feeling ~ which pre-empts an action.

Put simply: Event + Thought = Feeling ~ Action.

This provides a useful basis for helping young people to think about their actions. Many young people are unaware that they are complicit in the creation of their feelings. They are more inclined to believe that feelings are just things that happen, that take them over and cause them to do things.

This is to some extent true, especially with some of the stronger emotions. For instance, the startle reflex may precede thought. However, in many instances, the thought precedes the feeling.

Helping people to understand how they construct their behaviour is empowering. Discussions then move away from being interpreted as moral judgments, and become a discussion about choice. This shifts the focus from blame toward outcomes. Put simply: ‘What do you want?’ and ‘How do you get it?’

Engaging young people in a discussion about their choices, rather than their inherent goodness or badness, sends an incredibly powerful message. Instead of condemning a student for not doing their homework, a teacher might use an approach along the lines of ‘Yes, you failed to do your homework. Perhaps you always fail to do your homework. But this is your choice. You can change. You can employ a different set of coping strategies that will enable you to complete your homework, or at least, will give you a chance of completing your homework.’

‘The classroom activities are aimed at encouraging discussion between teachers and students about ‘choice’, ways of implementing ‘choices’ and strategies for coping with these ‘choices’.

Chris began to think about coping styles in terms of helpful and unhelpful. Using alcohol and other drugs in harmful ways to relieve stress was clearly an unhelpful coping strategy. For many dependent users, it had dominated, and even destroyed their lives. Working with these people, made Chris wonder about the coping strategies of young people. He believed that coping styles were learned. Some people learned predominantly helpful coping styles. As they became older, they became more proficient at managing their stress and their inter-actions with the rest of the world. Unfortunately for others, like the drug dependent patients with whom Chris was working, they learned predominantly unhelpful coping strategies. Their lives became increasingly difficult.

Chris decided to do some research with young people. Unfortunately, Chris passed away before his research could be published but nevertheless his findings provide an insight into helping young people. After interviewing nearly three hundred 15 year old students, Chris concluded there were basically eight (8) styles of coping. These are listed below, with short statements that characterise those styles.

Philosophical coping

• I try to see the funny side of things.

• I try to believe positive or good things about myself.

Problem-focused coping

• I just set my mind on what I had to do next.

• I tried to change the mind of the person in control of the situation.

Self-blame / culpability

• I realise I caused the problem.

• I kept others from knowing how bad things were.

Denial

• I tried to keep my feelings to myself.

• I went on as if nothing had happened.

Orientation to others

• I talked to someone to find out more about the situation.

• I tried to help others who were in need of help.

Self-care

• I tried to get plenty of sleep.

Acting out / loss of patience

• I was angry with those who caused the situation.

• I tried to make myself feel better by eating, drinking alcohol, smoking, using drugs or medication.

Composure

• I didn’t let the situation get to me.

• I made myself not worry or be upset.

The first implication is important in terms of managing the behaviour of young people. When discussing a young person’s behaviour, adults often refer to the behaviour as good or bad. This is a moral judgement. However, rather than interpret this as a judgement about behaviour, young people tend to interpret moral judgement as about them, the person. In other words, they are either intrinsically good or bad.

Instead of passing moral judgements, parents and teachers will be more effective if they engage in a discussion about choice. They can best do this when they have helped young people to understand how they construct their behaviour. A useful starting point is to borrow an equation from the field of rational / emotive therapy. It is simply: an event + an interpretation = a feeling ~ which pre-empts an action.

Put simply: Event + Thought = Feeling ~ Action.

This provides a useful basis for helping young people to think about their actions. Many young people are unaware that they are complicit in the creation of their feelings. They are more inclined to believe that feelings are just things that happen, that take them over and cause them to do things.

This is to some extent true, especially with some of the stronger emotions. For instance, the startle reflex may precede thought. However, in many instances, the thought precedes the feeling.

Helping people to understand how they construct their behaviour is empowering. Discussions then move away from being interpreted as moral judgments, and become a discussion about choice. This shifts the focus from blame toward outcomes. Put simply: ‘What do you want?’ and ‘How do you get it?’

Engaging young people in a discussion about their choices, rather than their inherent goodness or badness, sends an incredibly powerful message. Instead of condemning a student for not doing their homework, a teacher might use an approach along the lines of ‘Yes, you failed to do your homework. Perhaps you always fail to do your homework. But this is your choice. You can change. You can employ a different set of coping strategies that will enable you to complete your homework, or at least, will give you a chance of completing your homework.’

‘The classroom activities are aimed at encouraging discussion between teachers and students about ‘choice’, ways of implementing ‘choices’ and strategies for coping with these ‘choices’.

Customers who bought this also bought:

All About Anxiety Discussion Cards |

Your Choice: Stress Programme |